The Prosecution is Obligated to Help Prove Your Innocence

‘The Prosecution is Obligated to Help Prove Your Innocence’, or ‘The Requisite Duty of Disclosure by the Police and Prosecution about Any Material that Would Help the Defendant’.

Article by HH Solicitors North Shields

It sounds strange, doesn’t it? Dramas have conditioned us to believe that the courtroom is an antagonistic stage where the prosecutors deliver their evidence and the defendants must either disprove their arguments or display their own evidence gathered by their own resources.

In reality however, the working practices of the police and Crown Prosecution Services are supposed to assist the defence in the timely preparation and representation of their case and to enable the court to focus on the important issues in the trial. It is mandatory that the defence have access to all the evidence the prosecution have before even the trial begins, nothing is supposed to arrive as ‘surprise new evidence’ that dramatically proves guilt or innocence, much as entertaining TV that would be.

This is known as the duty of Disclosure.

Failures in Disclosure causes cases to collapse instead of closing into conviction

Sadly public perception and police and prosecutor careers are conditioned into believing that more convictions are better. It is understandable to be tempted not to give the opposing party any new evidence that would help them. In some instances, maybe this actually did put the guilty behind bars. But in more cases, failure to disclose all relevant evidence is a miscarriage of justice.

People who are otherwise innocent may be convicted and, for those who are actually guilty, the obvious bias casts future doubt on the evidence gathered by the justice system.

The foreword to the National Disclosure Improvement Plan 2018 states:

The legitimacy of our criminal justice system relies on the process being fair and even-handed. The public rightly expects to see the guilty convicted, but it is equally important to avoid the wrongful conviction of the innocent.

The disclosure process provides a crucial safeguard within the system. The police have a duty to follow all reasonable lines of enquiry, whether they point towards or away from the suspect. Prosecutors must provide the defence with any material that undermines the case for the prosecution or assists the case for the accused. Proper disclosure is vital for there to be a fair trial.

Criminal and Procedure Investigations Act (CPIA) Disclosure sets out a code of practice for police and CPS lawyers to disclose evidence to the defence that may undermine their case or be helpful to the defendant.

What are the ways Disclosure can cause a case to collapse?

From the Prosecution Data Tables:

Disclosure reasons: These are reasons identifying where an issue with the disclosure of unused material occurred, including timeliness or failure to provide material. The disclosure reasons can be disaggregated to provide more detailed analysis of the reason for the non-conviction outcome.

D77 Police/Investigator fault, including the timeliness and quality of disclosure – this reason applies when issues arising in the unused material were not dealt with adequately by the investigator, including failure to bring material to the attention of the prosecutor in a timely way and failing to provide schedules or requested material.

D78 CPS fault, including timeliness and quality of disclosure – this reason applies when issues arising in the unused material were not dealt with adequately by the prosecutor, including failure to review material and incorrect decision making on disclosure.

D79 Other party fault, including timeliness and quality of disclosure – applies when issues in the unused material were the fault of a third party, for example in failing to provide access to relevant material in a timely way or refusing to allow access to material required to enable any trial to be fair.

D80 No fault: Timeliness and quality acceptable but disclosure was a factor – applies if the case ended because of issues with the content of unused material but in circumstances where neither investigator, prosecutor or third party were at fault.

D81 No fault: Public interest immunity issues – applies if the case is stopped because disclosure of material is required which, because of its nature, would have the effect of disclosing that which the prosecutor considers should not in the public interest be disclosed.

According to the prosecution records published by the Crown Protection Service, from 2nd Quarter of 2020 to 1st Quarter of 2021 (until 30 June 2021), Disclosure reasons has caused the non-prosecution of 1,648 cases to date.

Of these, here is the breakdown of the year rolling year to date reasons for disclosure non-conviction outcomes:

• D77 Police/Investigator cause including the timeliness and quality of unused material

= 913 cases

• D78 CPS cause, including the timeliness and quality of unused material

= 134 cases

• D79 Other party cause, including timeliness and quality of disclosure

= 144 cases

• D80 No fault: Timeliness and quality acceptable but disclosure was a factor

= 430 cases

• D81 No fault: Public interest immunity issues

= 39 cases

Total = 1660 dropped cases

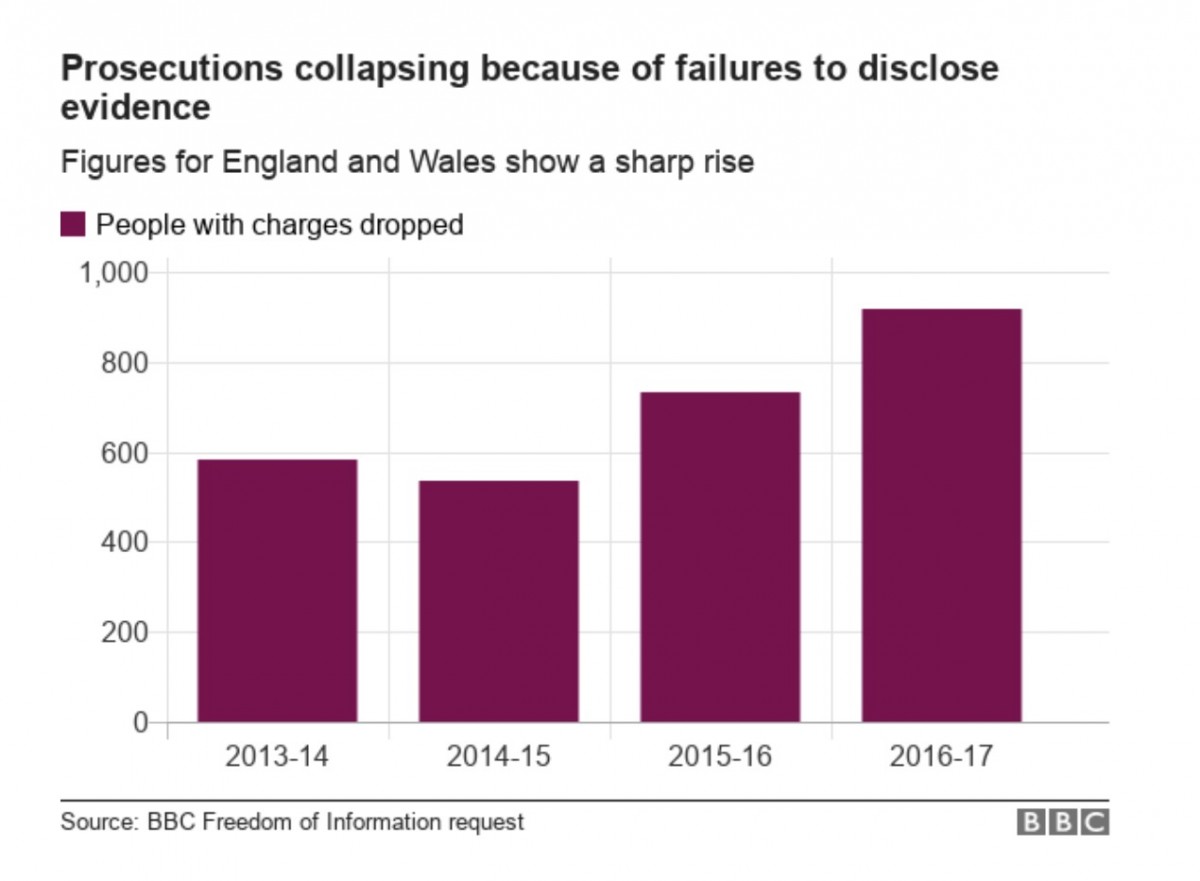

This is a massive number that has doubled the rate of cases dropped due to failure to since 2015-2016.

Case Examples for Failure of Disclosure

The Background for the National Disclosure Improvement Plan stated in its Background that:

Several years ago a murder case managed by South Wales Police resulted in an extensive investigation into police corruption. The trial relating to this corruption case collapsed due to failings in the disclosure of sensitive material. This resulted in several reviews of what had failed in the case, in particular one by the Independent Police Complaints Commission (IPCC) and one by HMCPSI, with both making a number of recommendations. A number of these recommendations were adopted within the criminal justice system by the police and CPS. Following the conclusion of the civil court case into the collapsed trial, the Home Secretary commissioned Richard Horwell QC to investigate the overall response to these two reports and the recommendations contained within them. He prepared a report called the ‘Mouncher Investigation Report’ which was published in July 2017. Overall he identified the need for a change in culture when approaching disclosure, making it a fundamental and continuing part of all investigations.

What is this Mouncher Investigation Report?

It is Richard Horwell QC’s report on the reasons for the collapse of the ‘Mouncher and others’ trial of 8 police officers in 2011.

It followed the wrongful conviction of three men for the murder of Lynette White in 1990. Evidence was uncovered that these police officers fabricated evidence against the three defendants.

Reinvestigation of the murder by officers unconnected to the South Wales Police, given the name “Operation Mistral” using new DNA technology, led to the charging of Lynette’s real killer who then pleaded guilty as charged.

These eight officers were then charged with conspiracy to pervert the course of justice in one of the largest police corruption trials in British history.

The trial subsequently then became an “embarrassment on the national scale” on its own and a “disclosure catastrophe” in which the prosecution mishandled and delayed disclosure of items that could have assisted the defence, even up to the point it was believed they had shredded documents. The documents with other 277 boxes of ‘potentially relevant material’ were found later but only after the defendants had already been formally acquitted.

The Mouncher Investigation Report made 17 recommendations for avoiding further controversies on the disclosure process. No longer would the process rely on ‘culture’ or ‘robust judicial management’ but instead prescribe a series of national standard forms, training, disclosure policy, and quality assurance work. There would be a record of defence requests for disclosure and responses.

“The use of phrases such as ‘strict interpretation of the disclosure rules’ must cease and any support for them actively withdrawn. The abiding principle must be ‘if in doubt disclose’ and nothing must be permitted to qualify or diminish it.”

Richard Horwell QC

More recent examples

In December 2018, the trial of a Liam Allan who faced 12 counts of rape and sexual assault was dropped when evidence emerged on a disc that the police had looked through of messages from the alleged victim pestering him for “casual sex”.

Another case in 2018 was dropped on the eve of his trial, as Oxford University student Oliver Mears was told that the prosecution made a ‘last-minute’ decision to drop the case after a diary that supported his case was uncovered after two years.

One recent embarrassment noted by the BBC was the £3 million diamond fraud trial involving The Only Way star Lewis Bloor and five others cleared of conspiracy to defraud between May 2013 and July 2014. 200 people were conned into buying coloured diamonds at 600% markup by cold-calling people (mostly old people) and encouraging an investment opportunity.

The CPS abandoned the prosecution after admitting that material that could have helped Mr. Bloor and other defendants had not been properly disclosed to defence lawyers. Narita Bahra QC called for CPS to conduct an inquiry into the case for its many disclosure failings. Among the suspicions was how The Metropolitan Police instructed an expert witness that had a contract with the force to auction jewelry and watched seized in raids and prosecutions.

After four weeks of trial, Judge Adam Hiddleston directed the jury to find the defendants not guilty. CPS spoke up that “As an organisation we remain committed to working with investigators, defence teams and courts to ensure we get disclosure right.”

Failure of disclosure leading to collapse of a case should lead not to the impression that the guilty are going to go free, but that they were probably innocent in the first place and being unfairly railroaded into a conviction.

In that same week, a £34 million money-laundering trial also collapsed after what the judge described as “systemic and catastrophic disclosure failures” on part of the CPS.

Handling the mass of evidence

It is not just white collar crimes that can collapse from failure to disclose. The pandemic has seen a rise in domestic abuse and rape cases, and if the CPS needs convictions then at no point should they take the risk of causing failure to convict by their own actions. If this means helping the defendants have all evidence that could help their case, then that is their duty.

Liam Allan, who is now director of The Defendant, a charity that provides support and information for defendants, stated that “police and lawyers are unable to cope with the vast volume of evidence generated by modern technology” and “they are using completely outdated systems.” With regards to The Defendant he states their mission “We are supporting people who are just stuck in the system and can’t get hold of the evidence that might help their case”.

“Chronic underfunding of the criminal justice system has led to understaffed and overworked police and prosecutors,” noted Ed Johnson, senior lecturer in law at the University of the West of England and co-editor of The Law of Disclosure: A Perennial Problem in Criminal Justice. “We should consider taking this out of the hands of the police to allow them to concentrate on other aspects of their job.”

Stuart Nolan, a defence lawyer and a defence lawyer and chair of the criminal law committee at the Law Society noted how police and prosecution lawyers did not have the required resources to sift through the extra evidence generated by modern electronic devices. “It can’t be done on the cheap and it has become increasingly difficult.”

Family law lawyers and defence lawyers warn that the courts may be at a breaking point from the rising number of cases collapsing because of police and prosecution failures to disclose key evidence. There is no easy solution, as prosecution also are not obliged to “accomplish the impossible”.

Paragraph 41 of the Code of Criminal Practice states:

“41. … It is not the duty of the prosecution to comb through all the material in its possession – e.g. every word or byte of computer material – on the look-out for anything which might conceivably or speculatively assist the defence.”

Oddly it is important to have a continuing dialogue between prosecution and defence to ensure that reasonable and proportionate searches can be carried out on “unused material” that is not retained for evidence.

As Richard Horwell stated in the Mouncher Report long ago:

On the evidence it is clear that very few emerge with credit: too many aspects of the investigation and prosecution were poorly managed. But my principal finding, from which much flows, is that bad faith played no part in the errors of either the police officers or the prosecution lawyers. It is human failings that brought about the collapse of the trial not wickedness.